More ‘bobbies on the beat’ is one of the most well-worn promises in British politics. The obvious way to deliver it: hire more coppers.

In 2019, the government’s Police Uplift Programme (PUP) aimed to do exactly that. PUP set a target to increase officer numbers by 20,000 (matching England and Wales’ all-time high officer numbers attained before the 2010 austerity drive). Recruitment support and financial incentives were put in place to ensure forces recruited and maintained the required officer numbers.

Many leaders in policing have, however, shared concerns that this was a flawed route to releasing more officers to the frontline.

In 2024, Sir Mark Rowley, the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, said:

“I could make really good use of that [money, not given to the Met, after it did not meet its PUP targets], recruiting police staff,” he said. “We’ve got too many police officers doing support jobs like HR because we’re geared wrong as a force between staff and officers.”

The logic runs like this: experienced police staff often spend decades in specialised back-office roles that officers rotate through only briefly. Filling those posts with career staff, not warranted officers, frees officers for front-line work.

Our analysis shows that more officers than ever are currently filling support functions in forces across England and Wales, supporting the idea that something has shifted in the way police forces are set up post-Uplift.

Where did the officers go?

On its own terms, it’s hard to argue that the PUP was anything but a success. A 20,000 bump in officer numbers was targeted and achieved at the national level. All but one force met its recruitment targets to support the policy. This was all achieved within the planned timescale, too. Nevertheless, Police leaders warned of a perverse incentive: forces might ‘park’ officers in back-office jobs to hit their Uplift quota and avoid penalties.

There are three broad issues with this:

- It is often an inefficient use of funds as officers typically cost more per hour than staff

- It reduces effectiveness by ‘deskilling’ functions by using ‘generalist’ officers rather than specialists

- It wastes officers’ powers and talentsas officers in those roles can’t use the full powers to protect the public that their warrant and training provides

Case study: support services in England and Wales

To test this idea, whether a ‘re-gearing’ of our forces has taken place, Leapwise has analysed trends in officer and staff numbers operating within ‘support services’ across the 43 territorial forces of England and Wales. Our data source is the Home Office’s Police Objective Analysis, which specifies the number of officers and staff working in a range of support services (the full list of role types categorised as support services is listed in full below this blog for reference).

Support services are clearly essential for effective policing. They include functions such as HR (including recruitment, training and retention) and ICT (which all officers clearly rely on increasingly – and are often frustrated by!) And for most of these functions, a warrant card is neither a necessary nor sufficient condition for effective delivery. As Sir Mark has argued, having police staff in these functions is generally more productive and can release a proportionately greater number of officers to the frontline.

There are minor exceptions and, in some support services, officer roles are clearly essential. For instance, it makes sense for officers to be involved in ‘training’ and certainly ‘Force Command’ role categories. However, in most areas we would expect forces to want to minimise officer numbers.

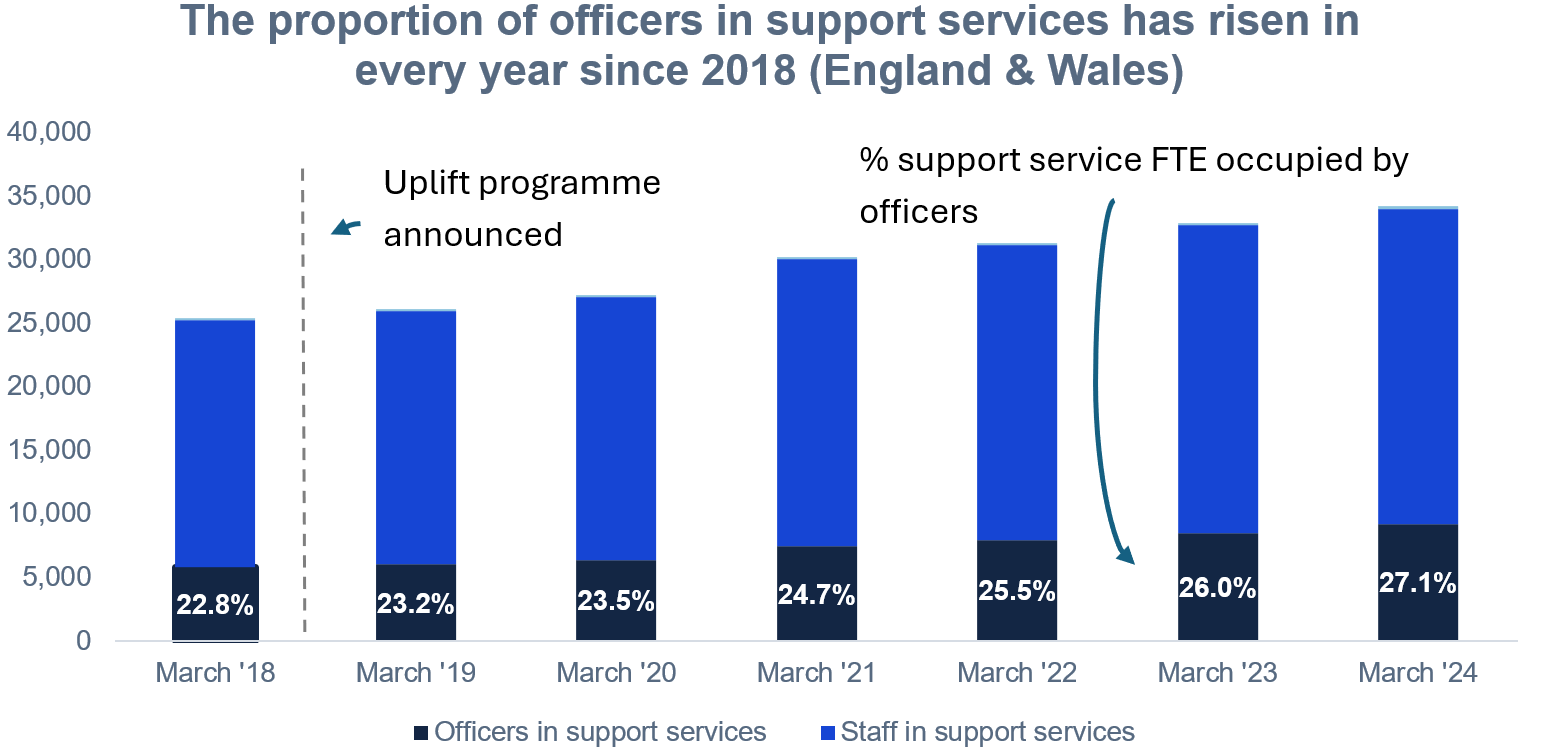

Looking at the overall figures of officers and staff in support services, there is a clear upward trend in both staff and officer numbers, reflecting the overall growth in police officer and staff numbers after the deep reductions from 2010 to 2018.

The bigger shift, however, is arguably a major increase in the proportion of officers in these roles. Across the period from March 2018 to March 2024, the number of officers working within support functions almost doubled, from around 5,700 officers in March 2018 to 9,200 in 2024. Over the same period, the proportionate rise in staff numbers was far smaller, rising from around 19,500 to just under 25,000. This equates to a 4.3% increase in the proportion of support service roles fulfilled by officers over the period. The rising tide of the PUP lifted all boats within support services, but officer numbers rose by more.

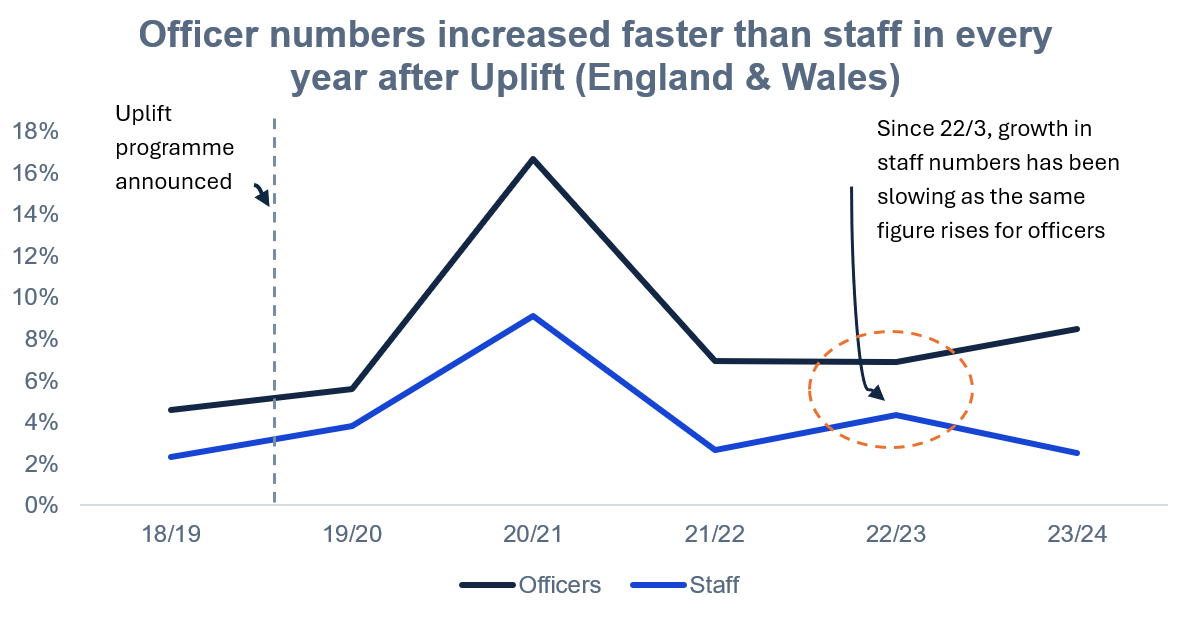

Looking at the rates of change reinforces this conclusion. In every year since the Uplift programme began, the rate of increase in officer numbers has outstripped the rise in police staff numbers.

In just one year, between 2020 and 2021, the number of police officers jumped from 14 to 17% of all staff working within support services. This was almost a one-fifth increase in just one year. Since FY 2022/3, the rate of increase in officer numbers has been going up, just as the rate of increase in police staff numbers is going down.

We are worried that this trend may continue and accelerate. Forces we work with face ongoing budget pressures, but still face severe financial penalties for failing to maintain officer numbers. So, while they know that putting officers in support roles is inefficient, leaders must either do so or allow these critical functions to stop doing vital work (therefore providing less support to busy frontline officers and undermining overall productivity).

Police Objective Analysis – the full list of support services categories is:

- Human Resources

- Finance

- Legal Services

- Fleet Services

- Estates/Central Building

- ICT

- Professional Standards

- Press and Media

- Performance Review/Corporate Development

- Procurement

- Training

- Administration Support

- Force Command

- Support to Associations and Trade Unions

- Social Club Support and Force Band

- Insurance/Risk Management

- Catering

What next?

In a later blog, we will extend our analysis to look at services closer to the frontline, such as custody, to see whether these trends appear there too. And we’ll also look at solutions to this tricky situation.

We are keen to hear from our colleagues in forces on this issue: what has your experience been in the Uplift and post-Uplift period?